The Mystery of the Millipedes: New Fossil Finds Shed Light on Early Ecosystems

Imagine a tiny, armoured train with a hundred pairs of legs marching along, moving like a small wave through the loam and the dirt as it searches for decaying matter to feed on. It encounters something unknown and, feeling threatened, immediately curls its long, segmented body into a tight, rock-hard spiral. Its tough exoskeleton and hard plates protect it from predators, giving it the ultimate defence mechanism. This is the signature move of the millipede. Millipedes, or “shongololos” as they are affectionately known in South Africa, are arthropods that play an important role in the ecosystem as decomposers, breaking down decaying plant matter and recycling nutrients back into the soil. But what if these vegetarians changed their diets to rotting flesh in times of environmental stress?

Millipedes are fascinating creatures with a long history on Earth. The ancestors of the modern-day shongolololo have been around since before the time of the dinosaurs; millipedes are believed to have evolved around 430 million years ago. Their ancestors were some of the earliest animals to venture onto land, and they have been evolving and diversifying ever since.

However, despite their apparent abundance, millipedes have a sparse fossil record, probably because most died on the surface and degraded too quickly. For this reason, it is exciting that a recent discovery in South Africa has shed new light on these creatures’ history. Scientists have found the fossilised remains of four new millipede specimens preserved alongside prehistoric four-legged vertebrates (called ‘tetrapods’) which, together with two previously reported millipede-tetrapod associations, offer a glimpse into their ancient ecosystem and possible explanations for these associations.

The discovery was made by Dr David Groenewald, Prof Jennifer Botha and Prof Roger Smith, a team of palaeontologists from the University of the Witwatersrand, who were studying rocks from the Main Karoo Basin of South Africa that were formed during the Early Triassic (about 250 million years ago). This was a time when the Earth was recovering from a major shift in climate and ecosystem collapse that led to the worst mass extinction event ever recorded.

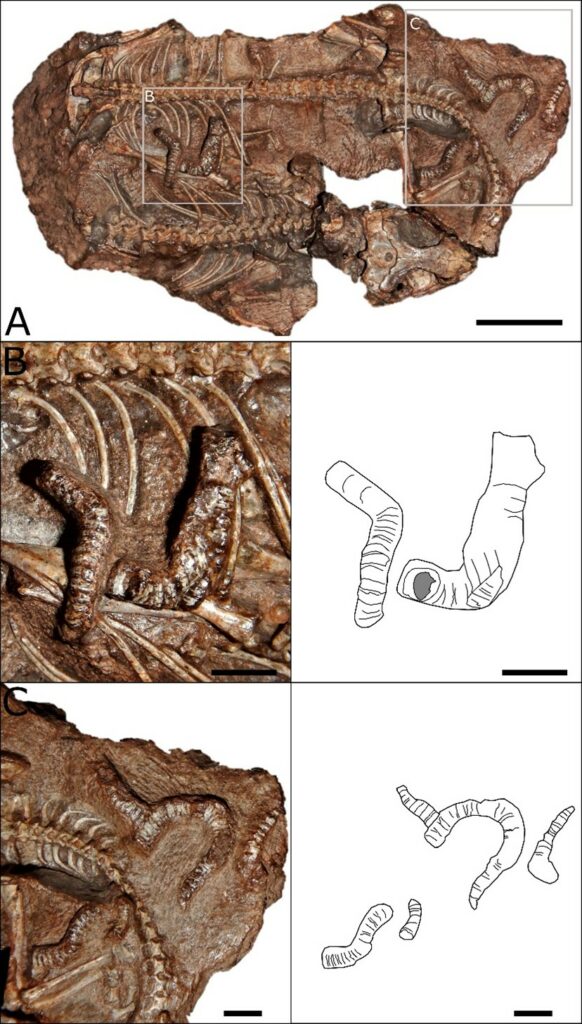

The fossil remains of the tetrapods from the Karoo Basin are especially significant because they come from the Permian, Triassic and Jurassic periods and provide valuable insights into how mammals, turtles and dinosaurs originated and adapted to their environment. The fossilised remains of the millipedes from the Karoo, only a few centimetres long, all comprise elongated, cylindrical bodies divided into segments, which can be clearly distinguished from the remains of the tetrapod, as seen in the photographs throughout this article. Because they were trapped in a burrow in the soil along with the tetrapods, these millipedes were good candidates for becoming fossils.

But why were the remains of the millipedes and the tetrapods found together? The research team propose several possible explanations.

One possibility is that the millipedes were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time and may have been sheltering in the same burrow or protected area as the tetrapod when they perished together.

A second possibility could be that the tetrapod had been feeding on the millipedes – but if this had been the case, the millipede fossils would probably have been in disarticulated bits, rather than the preserved, fully-articulated portions that can be clearly seen.

The most likely explanation is that the millipedes were eating the decaying tetrapod. Modern millipedes are often thought of as eating rotting plant material, but they have been observed scavenging on decaying carcasses and are often found in the soil around the remains of animals. This discovery suggests that these prehistoric millipedes likely switched from eating plants to scavenging on decaying carcasses during the Early Triassic Period. This would have had a significant impact on the ecosystems of the time; millipedes would have been an important part of the ecosystem’s waste disposal system, preventing the build-up of decaying matter and promoting nutrient cycling. Additionally, the scavenging behaviour of millipedes may have influenced the evolution of other organisms that relied on decaying carcasses as a food source.

This is an important finding because it would provide new insights into the feeding habits and ecological interactions of early millipedes and help us to better understand how these creatures evolved and adapted to their environment.

The recent discovery of the new millipede specimens sheds new light on the ecology of the Early Triassic Period. Studying ancient ecosystems can help us better understand how they respond to environmental change and the impacts of human activities on the environment. This discovery also provides new insights into the evolution of life on Earth by studying the interactions between different species during different periods. As a result, we can develop more sustainable ways of living that are in harmony with the environment!