The Marine Isotope Stage 5 (~105 ka) lithic assemblage from Ga-Mohana Hill North Rockshelter and insights into socialtransmission across the Kalahari Basin and its environs

Title: Stone Tools and Social Networks in the Kalahari: How Early Humans Stayed Connected

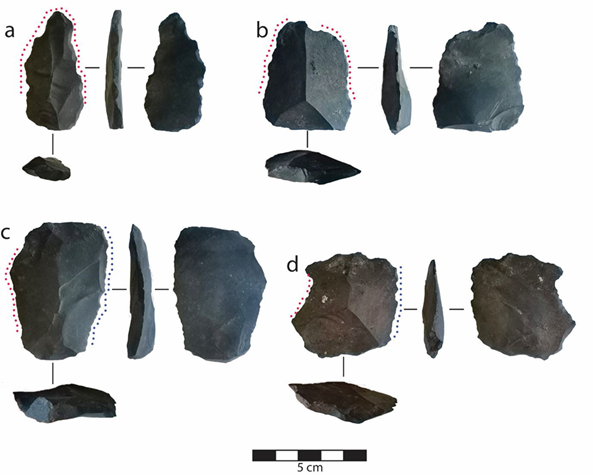

Imagine standing in the vast Kalahari, where the sun beats down on endless dry landscapes. It may seem like a tough place to live, but thousands of years ago, early humans called it home. They weren’t just surviving—they were connected, sharing knowledge and skills to help each other thrive. How do we know this? The answer lies in their stone tools. Crafting these tools wasn’t just about shaping rocks; it was a complex skill, likely passed down from expert to novice, over generations and between groups, revealing a network of knowledge-sharing and connection among ancient communities.

Uncovering the Past: Insights from Stone Tools

A recent study led by Dr Precious Chiwara-Maenzanise, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Human Evolution Research Institute (HERI) at the University of Cape Town (UCT), and co-authored by Drs Benjamin Schoville, Yonatan Sahle, and Jayne Wilkins, challenges long-standing beliefs about human interaction in the past. Published in The Journal of Human Evolution, the research shows that during Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 5, people in the Kalahari were not as isolated as previously thought.

For years, researchers believed that during MIS 5 (~130,000–74,000 years ago), human groups in southern Africa lived in isolation with almost no contact between communities. However, findings from archaeological sites in the Kalahari and adjoining regions—including Ga-Mohana Hill North Rockshelter, Erfkroon, Florisbad in South Africa, and White Paintings Rockshelter in Botswana—tell a different story. The stone tools uncovered at these sites share striking similarities in their manufacturing techniques and shapes. These consistent tool-making techniques across different sites is extremely exciting. “This suggests that people in the Kalahari weren’t isolated—they were part of a much bigger social network that shared ideas and ways of doing things,” explains Chiwara-Maenzanise.

Unlike other regions in southern Africa that experienced fragmentation during interglacial periods, the Kalahari Basin and surrounding areas exhibited greater connectedness during this time. Humans, by nature, need each other to survive—especially in harsh environments. In dry, unpredictable landscapes like the Kalahari, finding essential resources such as food and water would have been incredibly difficult alone. By maintaining shared traditions, early human groups were able to pass down crucial survival knowledge, helping them adapt and thrive.

The Thrill and Challenges of Fieldwork

Archaeological fieldwork brings the past to life. Imagine carefully excavating an ancient site and uncovering a tool that someone crafted tens of thousands of years ago. “It’s an incredible feeling, like shaking hands with the past,” Chiwara-Maenzanise describes.

However, working in the Kalahari presents challenges. The extreme heat and dry conditions make excavation difficult. “One challenge was working in such an extreme environment, but we were able to drive directly to the sites, which made logistics much easier,” she says. With careful planning, teamwork, and local knowledge, the research team successfully overcame these obstacles.

What’s Next for the Research?

There is still much to uncover about the lives of early humans in the Kalahari. The next phase of research will focus on how Earlier Stone Age and Middle Stone Age inhabitants sourced their raw materials and whether their usage patterns changed over time. “We also want to compare these two temporal periods and see how technological patterns may have changed over time in the Kalahari,” says Chiwara-Maenzanise.

Final Thoughts: More Than Just Tools

Stone tools tell us more than just how early humans crafted objects—they reveal the ways people connected, shared knowledge, and supported each other in challenging environments. This research compels us to rethink past assumptions about human isolation and instead appreciate the resilience and adaptability of our ancestors.

Even in the toughest conditions, humans found ways to stay together. And that’s something we can still relate to today.

The paper is available as open access, thanks to the publishing agreement between UCT and Elsevier.

Contact Author

Precious Chiwara-Maenzanise: precious.maenzanise@uct.ac.za

Reference for article

Chiwara-Maenzanise, P., et al. ” The Marine Isotope Stage 5 (~105 ka) lithic assemblage from Ga-Mohana Hill North Rockshelter and insights into social transmission across the Kalahari Basin and its environs.” Journal of Human Evolution (2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2025.103654

Funding

- Human Evolution Research Institute (HERI) at UCT

- GENUS: DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Palaeosciences

- French Institute of South Africa (IFAS)