How a South African palaeobotanist’s path was influenced by her vegetarianism

Dr Rose Prevec, one of South Africa's three palaeobotanists, shares her experience on the journey that resulted in the discovery of a fossil site with new findings.

Small bites

- Prevec discovered the “ultimate, once-in-a-lifetime find” sediment deposit in the karoo.

- The fossilised insects and plants discovered are new to the Permian period and date back 266 million years.

- The newly discovered fossils from the Karoo could be useful in understanding the peculiar reproduction of extinct plants like Glossopteris, which once overtook Gondwana.

The story begins

If Rose Prevec had been able to pursue her schoolgirl dream, one of South Africa’s biggest fossil sites might still be lying undiscovered. The dream was zoology, but there was a problem. Since the age of nine, Prevec had been a vegetarian and animal rights champion, and she knew dissection would be an insurmountable hurdle.

Could a zoology student possibly avoid having to cut up animals? Her mother asked a University of KwaZulu-Natal, professor. The answer was a flat “no”, so Prevec pursued her love of life sciences by studying botany instead.

Within eight years, she had her doctorate in plant pathology, but the career path still didn’t feel quite right. “I was printing a draft of my master’s dissertation on rust fungus in Kikuyu grass, thinking ‘I don’t want to do this’,” she says. And she knew there was another childhood itch demanding to be scratched: fossils.

Before long, Prevec was on the phone with Prof Marion Bamford at Wits University, asking if she could study palaeontology even though she had been denied permission to major in geology at the undergraduate level. “She just said, ‘Come’,” says Prevec, and a second doctorate followed.

Twenty-five years after that conversation with Bamford, with Prevec now a world-renowned palaeobotanist, the one-word reply from someone who went on to head the Evolutionary Studies Institute at Wits has acquired new significance.

That’s because Prevec has just announced her “ultimate, once-in-a-lifetime find”, an almost impossibly rich fossil deposit that fills massive gaps in knowledge about the evolution of the planet and the diversification of its life forms.

The discovery happened by chance during an otherwise unsuccessful 2009 field trip in the Karoo. “This outcrop appeared, and I yelled ‘Stop!’,” she says. “To me, it screamed fossil plants, and within minutes we were finding fossils.”

Several excavations later, she disclosed in the Nature journal Communications Biology that the find is a Lagerstätte: A sedimentary deposit that contains extraordinary fossils in a state of exceptional preservation.

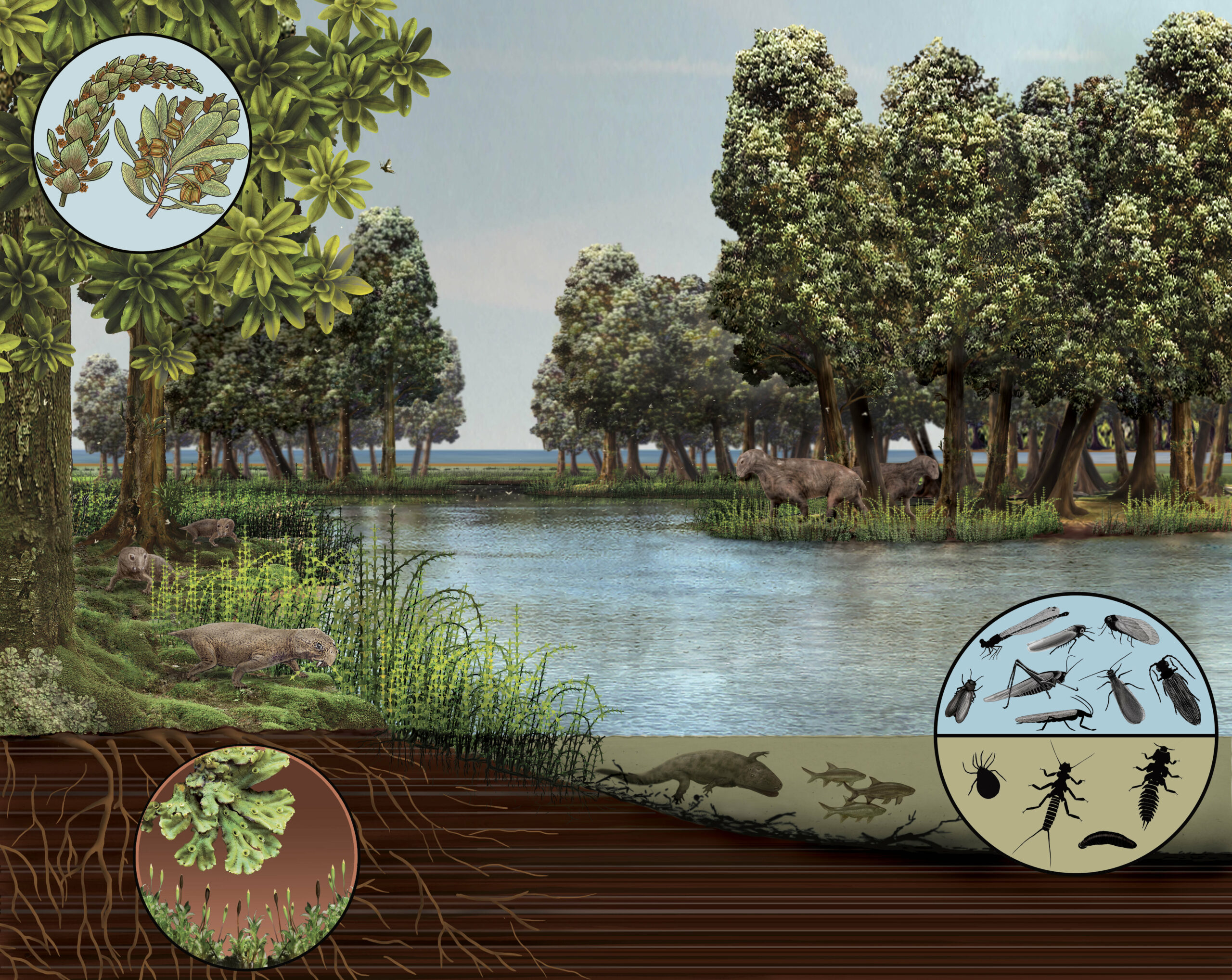

Most of the thousands of fossils Prevec and her team have uncovered plants and insects that are new to the Permian period in which the rock was formed or new to Gondwana.

The fossils are particularly rich in superb examples of a plant close to Prevec’s heart and the topic of numerous papers listed in her CV: Glossopteris, the tree responsible for South Africa’s rich coal deposits.

“I call it ‘my plant’,” she says from her office at the Albany Museum in Makhanda, where she is head of earth sciences. “It is very under-appreciated, possibly because it is a difficult plant to classify, and there is lots still to discover about it.”

The new Karoo fossils will help. Prevec hopes they will add layers of knowledge about a reproductive system she describes as “very strange” but which was clearly successful: Glossopteris “took over Gondwana”, she says, covering a swathe of southern Pangea.

The end-Permian extinction put paid to the plant and 70% of all terrestrial taxa. Still, Prevec says current climate change and the pressure on modern ecosystems have given new impetus to palaeobotanical work because understanding the past is increasingly important in informing efforts to save the future.

“This is the heyday of palaeo,” she says. “We’ve never had so many funding opportunities, and global interest has never been so intense.”

After discovering the Lagerstätte near Sutherland, Prevec had to wait seven years before her Albany appointment made it possible to start excavating. Funding since then from the National Research Foundation and the GENUS (DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Palaeosciences) network at Wits has allowed her to lead several expeditions to the outcrop, and she expects a flood of international interest in the thousands of fossils that have been transported to the museum. The first two papers on insect finds have already been published with Prof André Nel at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, a third has been accepted, and Prevec – 50 in December 2022 – expects to be preoccupied for the rest of her career by these and other Karoo fossils she has been finding.

She’s keen to attract students to what she admits is a rarefied field of study, saying it provides a rich opportunity to learn to do research. “It’s a good area for any life scientist or geologist, and good bursaries are available,” she says.

The picture isn’t quite rosy at the Albany, which she says is “grossly underfunded” in common with most South African museums. “I’m a one-woman show,” she says. Her CV provides the detail: she is responsible for “curation, research, outreach, administration, teaching, supervision of postgraduate students, management of the department, fundraising and heritage management”.

Prevec adds: “We rely on external funding for our research programme, and the positive aspect is that I have a lot of freedom in my research.”

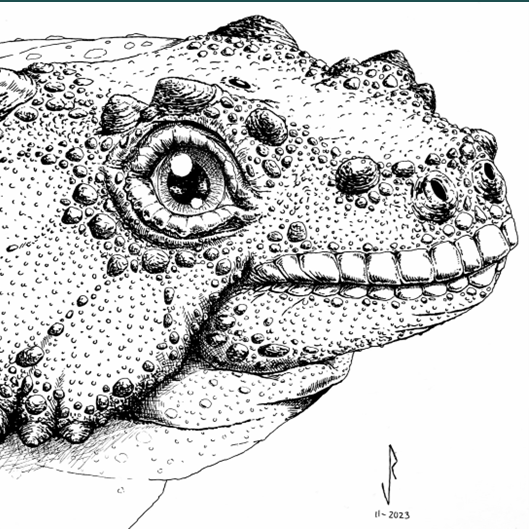

Makhanda (then Grahamstown) became Prevec’s home when her husband, Steve, was appointed as a lecturer (now professor) of geology at Rhodes University. The couple has two teenage sons, and Prevec relaxes by painting scientific illustrations. She has even visualised the lake shore where her Karoo fossils originated, populating it with plants (including her beloved Glossopteris), animals and insects.

Incidentally, the fossilised remains of insects don’t have the same effect on her as the thought of dissecting animal corpses or even the idea of swotting a mosquito. “Maybe that’s why I love palaeo,” she jokes. “All the animals are long dead.”