The prehistoric survivalists who know a thing or two about surviving the next extinction

Dr Jennifer Botha is on the hunt to find out why certain animals that lived hundreds of millions of years ago were able to survive some of the planet’s worst mass extinctions.

Small bites

- The end-Permian and the end-Triassic were two large mass extinction events that occurred within 50 million years of each other.

- Lystrosaurus, a squat-tusked herbivore dicynodont, survived the end-Permian extinction, while the early long-necked dinosaur Massospondylus lived through the end-Triassic extinction.

- To understand how Lystrosaurus and Massospondylus survived, Dr Botha has studied their bone microstructure to work out their changing growth rates.

The planet was almost emptied of life.

There was a time when death swept the planet. It nearly emptied the seas of life; on land, it killed maybe 70% of all species. This was when volcanic eruptions pumped CO2 into the atmosphere, causing temperatures to spike. Never in the planet’s history was there a point when life came so close to total annihilation. Today it is known as the Great Dying or the end-Permian mass extinction, which happened 252 million years ago, and its story is told in the rocks that lie across the hinterland of South Africa. But this story is not just about death, it is one of survival too. There were survivors of this dark time who even went on to prosper. They had an X factor that enabled them to hang on, and Dr Jennifer Botha wants to find out what this was. Working out what this X factor was could help in saving species today, just as the planet faces yet another extinction. It is a mystery that Botha is piecing together with the help of the fossil bone microstructure. The approach allows her to peel back time, and from magnified slivers of fossilised bone, she can peek into the lives of animals that lived a quarter of a billion years ago. “I can tell from the bone microstructure if an animal was a juvenile or an adult, how old it was when it died, and how quickly it grew. If it was growing fast or slowly,” explains Botha, Head of Karoo Palaeontology at the National Museum in Bloemfontein, South Africa. She is also a GENUS Grantee. “I can compare this to modern animals and growth strategies.”

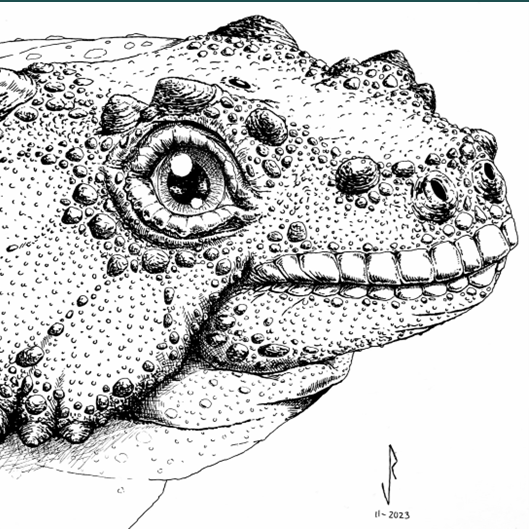

The work Botha is doing is called palaeohistology, the study of fossilised bone tissue and what allows her to do this are the unique finds palaeontologists are discovering at dig sites across the country. These dig sites don’t just tell the story of the Permian die-off. They are producing evidence of other extinctions that happened hundreds of millions of years ago. And a new site close to the village of Qhemegha, in the Eastern Cape, is providing a peek into the end-Triassic extinction that happened just 50 million years after the end-Permian extinction. “This site is giving us a perfect shot of before and after the extinction, and what is amazing is that there are very few sites around the world that actually preserve body fossils for this time period,” explains Botha. These sites show that life bounced back rapidly after these mass extinctions. One animal that survived the end-Permian extinction and then went on to prosper as a squat-tusked herbivore dicynodont called Lystrosaurus. “It was very abundant, and it seems to have found a niche and a way of living during the harsh times after the extinction,” says Botha.

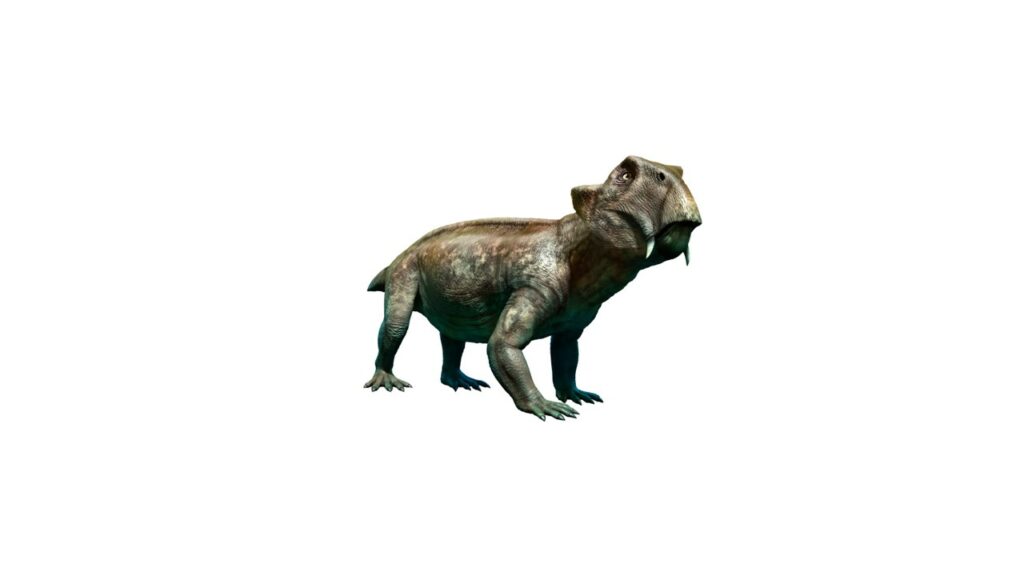

Another disaster taxon species that survived the later end-Triassic extinction was a herbivore called Massospondylus, a long-necked dinosaur that is common in the fossil record. Palaeontologists have found not only the eggs of Massospondylus but also the young and old embryos, which has helped Botha study how this dinosaur’s size changed under different conditions.

Botha believes one of the X factors that turned Massospondylus and Lystrosaurus into those ultimate mass extinction survivors was that they were generalists who could adapt to new conditions rapidly. “Those that went extinct were highly specialised they just couldn’t adapt quickly enough.” This quarter of a billion-year-old survival strategy could work today. However, the planet’s extinction event is far different from those in the Permian and Triassic.

The end-Permian mass extinction is believed to have occurred over a couple of hundred thousand years. The extinction we are now facing that was brought on by climate change is far more rapid. It kicked off at the start of the Industrial Revolution just 250 years ago. “What animals are going to survive the sixth extinction will be generalists, those that prey on a lot of different animals or eat a lot of different plants,” explains Botha.

As sites like Qhemegha produce more and more finds, our understanding of these deep extinction events is set to grow. With more specimens at hand, Botha wants to eventually focus on another period that saw a couple of lesser extinctions and, like today, suffered bouts of climate change. This Triassic period is bracketed by these two extinctions at its start and end.

But in between were climate shifts and smaller extinctions during a period that saw the change over of dominating taxa from therapsids to dinosaurs. Botha wants to link the growth patterns of these different taxa to the changes in climate conditions throughout the Triassic. That, she hopes, will help explain why the reign of the therapsids ended and dinosaurs began their long period of ascendancy.

“Because it’s not just as simple as one growing faster than the other,” she says.